If any term in writing is elusive, it’s voice. That sentiment is likely because voice seems subjective.

Voice and tone are often used interchangeably. However, one is static, and the other can change across different pieces of content.

Writers often speak of “finding their voice,” hinting at some unique quality that makes their writing sound like them. In the context of your content, this subjectiveness applies to your written assets having a consistent feel from one to the next.

And just as writers can begin to nail down common traits in their work that give a sense of their personas, your brand voice guidelines thread recognizable themes through your blogs, white papers, email copy and more.

Voice isn’t some enigma that you just have to intuit. In your written content, you make it concrete via harmony between several craft elements, such as diction and structure.

Why is voice important in writing?

The customer journey relies on a consistent story. You craft that tale with a voice that remains the same from beginning to end.

Imagine reading an amalgamation of pages from Twilight, Bad Feminist, The Hunger Games and A Game of Thrones. Not only would the disruption of plot and genre jar you, but also the shift between the perspectives of Bella Swan, Roxane Gay, Katniss Everdeen and GoT’s plethora of point of view characters would unsettle you.

Think of your brand as the protagonist in the story. Each chapter should feel like it pertains to the same character as you portray your organization more like a person than a corporation.

Defining voice ensures consistency and better positions you to explain your brand’s character to others, particularly when it comes to crafting creative briefs. Detailed voice stipulations allow in-house and third-party content creators to nail down this quality, leaving less margin for error.

Without these signposts, you can’t define your brand’s voice in terms anyone can understand, especially in the writing. As a result, you may start discussing it abstractly, knowing a written asset lacks the appropriate feeling without a means of diagnosing the issue. Or your CMO may take a completely subjective approach to voice, giving mixed signals when one piece of content receives a glowing review and another seemingly similar one lands in the rejection pile.

What aspects of writing create voice?

As mentioned earlier, the conflation of voice and tone often helps proliferate the belief that the former isn’t easy to map out.

Tone refers to a speaker’s attitude toward a specific subject. While tone is easier to intuit (though it, too, exists through concrete means), voice isn’t an element you can boil down to an adjective or two. Plus, tone can change from one topic to the next, but the voice remains consistent.

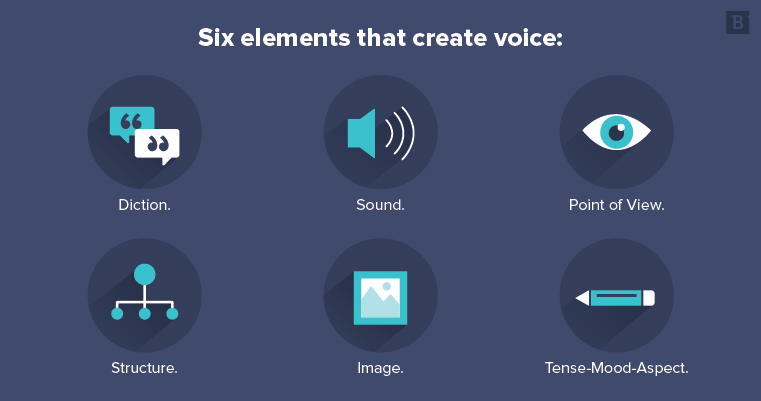

In the February 2017 edition of The Writer’s Chronicle, poet and nonfiction writer Sandra Beasley cited six elements that create voice:

- Diction.

- Sound.

- Point of view.

- Structure.

- Image.

- Tense-mood-aspect.

Her discussion and examples centered on creative works, but her main argument applies to all writing:

“In terms of a body of work, an oeuvre, your voice represents your dominant modes of decision-making,” she wrote.

For your content, voice is the sentence-by-sentence intent that makes each asset part of the same story. Whether you’re creating a new set of brand guidelines, refreshing old ones or considering how existing ones map to a planned piece of content, here is a look at how Beasley’s six craft decisions apply to your content writing:

Pay attention to diction

This point refers to the intent behind your word choice. Such decision-making applies from one word to the next in a blog and across all of your content.

You can consider diction in several ways, such as:

- Etymology: Word origins can affect reader perception and help you map sonic patterns.

- Sound: Syllable counts, stresses, rhyme, alliteration and the like help you select words that give your brand voice the kind and level of music it needs.

- Connotation: Words carry contextual meaning that can supersede denotation, such as your brand saying “affordable” instead of “cheap.”

Think about which lexicons fit your brand, and pivot each word choice to align to a typical vocabulary.

Also, if jargon suits for your brand voice, weigh how much is appropriate. Will your audience relate to jargon-dense paragraphs, or do readers need just a familiar phrase here and there to believe your authority?

This decision also pertains to whether you can woo your readers with buzzwords or if they’ll need fresher, emerging terminology.

Listen to sound

Not every brand voice embodies the movement of a symphony. Think about these sonic considerations:

- Phonemes: This term refers to the smallest units of speech. You can string together phonemes from the same categories to create music.

- Assonance: When you combine words that have the same vowel sounds, you use assonance. This tool is useful for slant rhymes, which occurs when words sound somewhat the same but aren’t sonically identical.

- Consonance: Working in the same manner as assonance, consonance applies to consonants.

- Alliteration: Sonic similarity in this case derives from repeated consonant and vowel sounds at the start of consecutive or near consecutive words.

- Rhyme: More familiar than the others in this list, rhyme is when you employ similar sounds at the end of words.

- Rhythm: When you create a pattern of sound, such as consistently arranging stressed and unstressed syllables, you establish a rhythm. Flow in writing can derive from rhythm.

How can you vary and use these tools to fit the voice you hope to create? How often should they appear?

Organizations like alternative investment advisors and managed IT services providers may have readers who focus on the stats more than the sound of the writing, while travel agencies and beauty product suppliers may need to mimic physical beauty through content that reads more like a song.

Determine a point of view

Your choice of first-, second- or third-person POV can produce voice in various ways.

One consideration is the perceived distance between speaker and reader.

First person

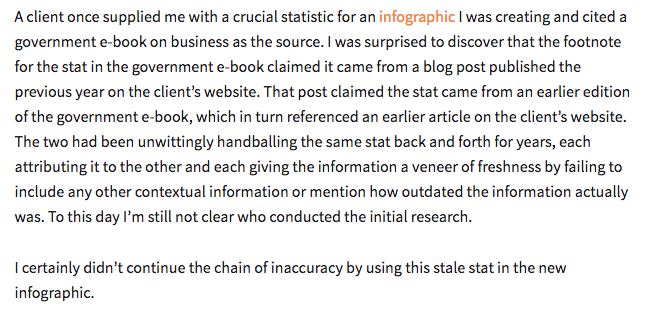

This POV often appears with more casual voices, as it can identify the speaker with the readers. Jonathan Crossfield, chief consulting editor for Chief Content Officer magazine, took this approach in his piece covering the importance of fact-checking:

With his anecdote, Crossfield establishes his authority to speak on a subject, or ethos. He tells readers that he, too, has seen the perils of verifying statistics while creating content, and from those experiences, he’s learned some valuable lessons worth sharing.

First-person POV can also be singular or plural. The collective “we” can highlight written content as the voice of the people who make the company rather than a singular, albeit informed, representative.

Second person

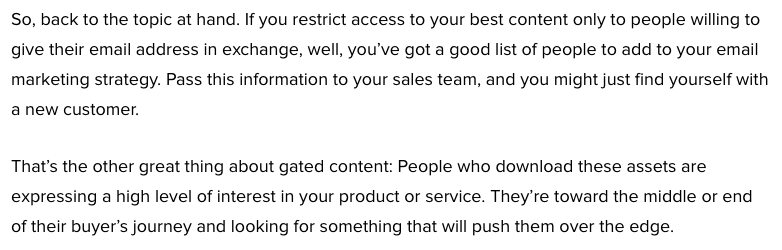

You can use this POV to implicate readers with a direct address, making them feel like part of the conversation or giving commands through the imperative mood. Check out this example from our best practices for your gated content:

The approach here is to talk to readers, with the POV aiding the conversational voice and helping the audience visualize the recommendations at their businesses, not some ambiguous white space.

Third person

This POV can feel detached from a personal connection because the voice appears to know all, and the perspective focuses on the organization as a corporate entity. Wells Fargo’s AdvantageVoice blog employs this perspective:

The firm speaks about itself and its target audience in the third person. While individuals within the organization, including the post authors, boast knowledge and insights on market movement, the Wells Fargo name and authority that go along with it resonate with readers who want accurate and definitive information.

More formal organizations might similarly opt for third-person POV to reflect all-knowing authority rather than establishing ethos through commonality.

Build similar structures

Voice also has visual components. At the broad level, how the copy in your article looks reflects your brand.

For instance, content that looks like a wall of text can appear more formal and even stuffy to readers. The inclusion of H2 and H3 subheads, bulleted lists, inline images, pull quotes and embeds like tweets and YouTube videos can present a more casual feel in addition to improving readability.

Structural intent also applies at the sentence level. Beyond avoiding overuse of right-branching construction (e.g., “Charley Content greets visitors”) to alleviate sonic monotony, pay attention to syntax consistency to make certain the voice remains authentic. If one writer worships Hemingway and another is fond of complex, interruptive syntax, readers will notice the variation.

Don’t forget sentence structure determines pace. Excitable brand voices full of energy won’t reflect that personality with a plethora of long sentences chock full of commas slowing the reading speed.

Describe with relevant descriptions

In terms of content marketing, imagery discussions can relate to voice regarding the examples you use. While you could speak in a figurative sense, your readers are likely more interested in tangible benefits and takeaways, especially if they must eventually use points from your assets to gain executive buy-in for your products and services.

Voice authority arises from example scenarios that are specific to your target audience. If your solutions appeal to superintendents, examples in your content should function in the business of education, rather than just generic benefits that could apply to any organization.

Our hot takes on how to grow Instagram followers for free include examples from Cisco and Purina. While anyone can learn a lot about building a following from Chrissy Teigen and other burgeoning celebrity profiles, insights from her profile don’t necessarily translate to an organization’s Instagram.

If you do go into the figurative realm, use metaphors, similes and allusions that gel with your brand voice and readers. References to classic literature may not be as appropriate as allusions to reality TV shows when writing to 20-something readers.

Imagery relays how a speaker makes comparisons in the world. The cybersecurity firm that likens its solutions to a Macedonian phalanx is much different than one that employs an association with a force field.

Maintain your tense

Content typically appears in past or present tense. Here are considerations for both:

- Past tense: Describes events that occurred before the time of writing. It can also present authority and truth by indicating the events as having happened.

- Present tense: Gives writing urgency through an in-the-moment feeling. With the inclusion of time-bound data in your content (i.e., X percent of people clicked paid ads in 2017), this tense can prove less useful, so past tense is likely more appropriate.

Outside of switching tense for example scenarios or describing future trends and benefits, keep your tense the same.

However, if your brand rules adhere to a style guide, be aware of specific conventions. Associated Press style’s broadcast guidelines for news stories, for example, mandate present or future tense in story leads and present perfect for headlines.

What should you do with your voice?

No, this part is not a suggestion that you audition for a reality TV singing competition. But it is a recommendation to put your voice on display.

Once you’ve determined how you want to use each craft element to create your brand voice, write the guidelines down as part of your brand rules.

Don’t forget examples, which can serve as a starting point until your content creators can intuit how to replicate the voice in every piece of content they produce. If certain words are preferred, provide a list. If the desired structure includes inline images, say how often they should appear.

Diction, sound, point of view, structure, image and tense are concrete markers for achieving the voice you want in all of your content, so lay out the specifics to dispel confusion.